Sow feeding during lactation

Lactation is the most demanding period in the reproductive cycle of a sow. Modern sows can produce more milk per kilogram of body weight than a dairy cow and this may still not be enough to maximise piglet growth during the lactation period. Optimal management during lactation is crucial to successfully produce heavy, uniform piglets at weaning. This article discusses some aspects of nutritional lactation management.

Milk production is determined by the ‘pull’ of piglets and the ‘push’ of feed

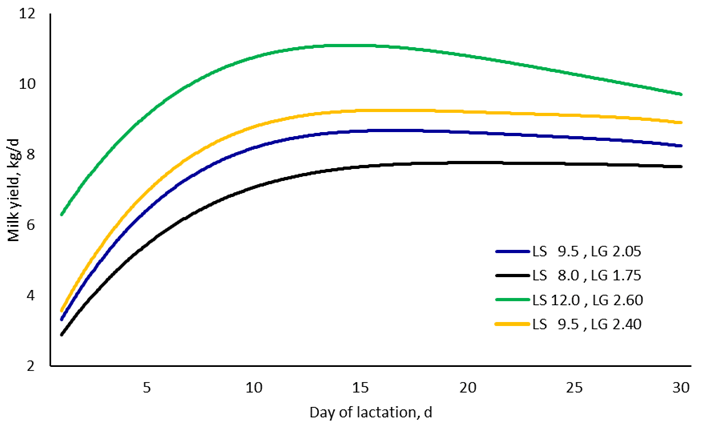

Milk production of the sow is stimulated by the suckling demand of the piglets - PULL. Figure 1 shows the daily milk yield from sows suckling different numbers of piglets and/or with different litter growth rates. Increasing the number of piglets can increase milk production (green line). In addition, increased litter growth can also stimulate milk production, and vice versa (yellow line vs blue line). To optimize milk production of the sows, piglets must be strong and healthy at birth, and they must stimulate the udder as soon as possible. All the teats must be stimulated within the first two days after farrowing, as non-stimulated teats will produce less milk and may even become completely non-productive. This is especially important for first parity sows as the udder needs to be activated to also produce enough milk in the subsequent parities.

Figure 1 Milk production of sows related to litter size (LS) and litter growth (LG) (Adapted from Hanssen et al 2012)

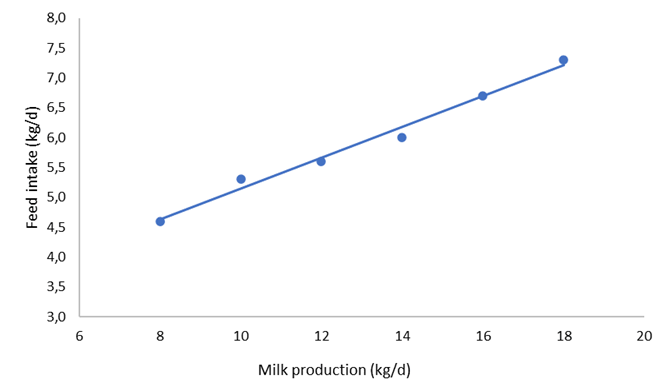

The amount of feed consumed by the sows can also stimulate milk production - PUSH. Figure 2 shows the correlation between the amount of feed consumed (kg/day) by the sow and milk output (kg/d) from data collected at the De Heus Swine Nutrition Centre, De Elsenpas. Milk output increases almost linearly as feed intake increases. This means that the feed allocation to the sow must match the milk yield requirements of the litter of piglets. Sows with a few piglets may need less feed than sows with more piglets.

A common problem experienced on farms is hard, or inflamed, udders before, or just, after farrowing. This can be due to feeding the sow too much during the transition period. Providing high protein and energy levels to the sow stimulates milk production. Before birth or if the piglets are too small or weak and not able to empty the udder, then milk will build up in the udder. This causes the udder to swell up and become hard or even inflamed which is detrimental to sow welfare. The sow then responds physiologically by slowing down, or even stopping, milk production which will be detrimental to milk production later in lactation. To prevent this situation from occurring, it is advisable to adopt a feeding strategy around farrowing that stimulates milk production that corresponds to the demand of the piglets. This can be done by using a transition diet and adjusting the feeding schedule according to the energy level of the diet, or not changing over from the gestation feed to the lactation feed until after farrowing.

Figure 2 The correlation between feed intake and milk production (data from Swine Nutrition Center ‘De Elsenpas’, De Heus)

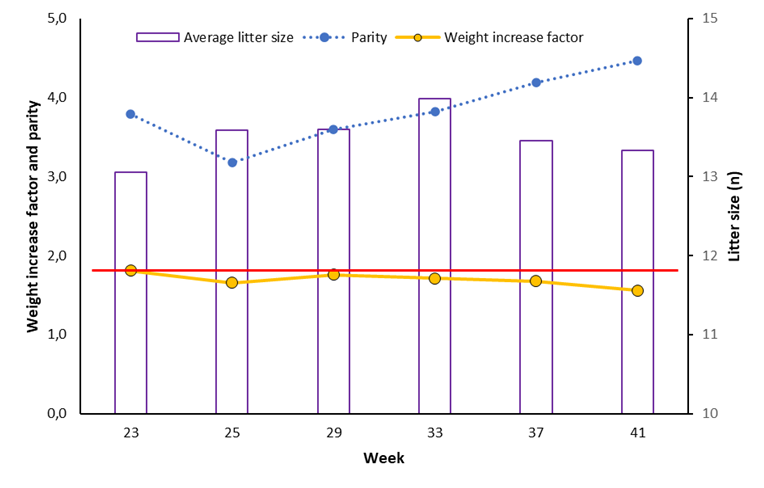

A milk scan can be done to assess the milk production of the sows. This is done by weighing piglets around birth and then again at 7 days of age. The weight gain of the piglets gives a good indication of how the milk production has begun and helps in making decisions on the right feeding strategy. The aim is for the weight at 7 days of age to be 1.8 times the birth weight. For example, a piglet weighing 1.5 kg at birth should weigh 2.7 kg at 7 days of age.

Figure 3 shows the results of milk scans done on a farm during 6 different weeks. The weight increase factor which is calculated by dividing the 7-day weight by the birth weight, is given on the vertical axis on the left hand-side along with the average parity of the sows that farrowed that week. The red line shows the weight increase factor target of 1.8. Litter size is given on the vertical axis on the right-hand side. For weeks 23 and 29, the target was achieved, but for the other four weeks, the weight gain was lower than the target. This can indicate that the sows were not producing enough milk. The reason for this can be investigated and a solution can be put in place to improve the situation.

Figure 3. An example of a milk scan done in 6 different weeks. The bars show the average litter size, the blue line the average parity and the solid yellow line the average weight increase factor. The red line defines the norm of 1.8.

Figure 3. An example of a milk scan done in 6 different weeks. The bars show the average litter size, the blue line the average parity and the solid yellow line the average weight increase factor. The red line defines the norm of 1.8.

Nutrients for milk production

To produce milk, sows use nutrients from the feed as well as their body reserves. Drawing from body reserves is not a problem if the sow is in the correct (good) body condition at farrowing. Body weight loss is made up of loss of fat and loss of protein (muscle). Fat is an easy-to-use energy source, and easy to recover which means it usually does not affect reproductive performance too much. In contrast, excessively high protein (or muscle) losses in lactation can have a detrimental effect on reproductive performance in the subsequent cycle. Normally a lactational weight loss of around 10% to 12% is considered acceptable if the sow is in good body condition at farrowing.

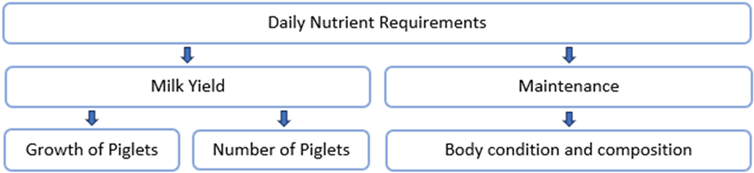

The nutrient requirements of a lactating sow are determined by the nutrients required for maintenance and milk yield (Figure 3). The requirements for maintenance are determined by sow body condition and body composition at farrowing. The requirements for milk yield are determined by the growth and number of suckling piglets usually combined in a key figure called Daily Litter Growth, that is used to determine the requirements for milk yield. To calculate if the requirements are being met, we must know the nutrient intake per day which is calculated from feed intake (kg/d) and feed composition of the feed being fed. The difference between the nutrients supplied and nutrients required will determine the actual milk yield and what body reserves the sow will use during lactation. Regularly checking the body condition of sows helps in determining the optimal feeding strategy on a farm and therefore optimises sow performance.

Figure 4 Schematic view of factors determining the daily requirements of a lactating sow.

Figure 4 Schematic view of factors determining the daily requirements of a lactating sow.

What you see is not always what you get!

Due to the selection for lean growth of finisher pigs, modern sows have lower fat reserves and more muscle compared to sows from 10 years ago. This is easy to see when visually scoring the body condition. In Figure 5, the sow on the left has an average body shape, but high fat reserves. The sow on the right looks similar to the sow on the left and when scored visually, would be classified as being fat, while she has low-fat reserves. The genetically leaner sow will be more dependent on (mainly) energy from feed than the genetically fat sow. To distinguish between these sows, the visual body condition score should be combined with backfat measurements.

Figure 5. The relationship between visual body condition scoring and actual body reserves of sows.

Tips and tricks to optimise milk production

For optimal lactation performance of the sow:

- Make sure sows are in optimal condition at farrowing: check your gestation feeding strategy.

- Pay attention to the nutritional transition from gestation to lactation.

- Feed sows as close to their requirements as possible.

- More is not always better.

- Try to manage the climate in the farrowing room to optimise feed intake.

- Monitor sow feed intake and piglet growth to define the correct feeding strategy in lactation.

- Make sure sows are drinking enough. As a guide, the water flow out of the drinking nipple should be 3 litres/minute.

- Try to balance the climate between being warm enough for the piglets and cool enough for the sow.

- Provide a warm, nest area for the piglets.

Should you require more information relating to sow feeding during lactation please contact your De Heus Technical Specialist - https://www.deheus.co.za/meet-our-team/.