Coccidiosis in Poultry

Whether you are considering raising your own chickens for the consumption of meat and eggs or have an established commercial flock, protecting your birds from disease will help you unlock and maximise the production potential of your flock and profitability. One such disease is widely known as one of the major causes of poor performance and loss of production in poultry due to the damage caused in the intestinal tract. Coccidiosis is a common parasitic disease of the intestinal tract caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Eimeria and can have devastating effects on profitability.

The parasitic organism attaches itself to the intestinal lining and destroys the intestinal cells. Using up some nutrients as well as preventing the host from effectively absorbing much-needed nutrients vital to the survival and performance of the bird. The parasites are host-specific and can potentially open the door for other pathogens to invade.

How does this happen?

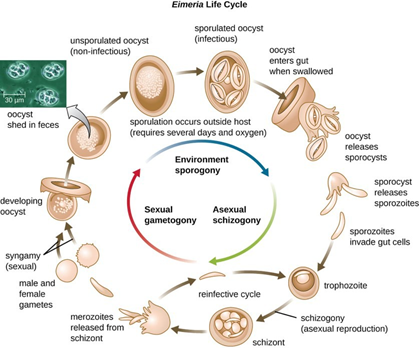

The life cycle is direct, and Coccidiosis starts with an ingested microscopic egg (oocyte), reproduction in the host, and completion of a new generation of oocysts 4 - 7 days later and then passes through the droppings of the bird. These oocysts can be present in the environment wherever poultry are/were raised because they are capable of remaining dormant in soils for up to a year and will only become infectious (sporulate) when conditions support their survival. Each species is specific to a given host, and those that parasitize poultry are not capable of establishing infection in other hosts, such as cattle and sheep.

Sporulation is generally more prevalent in wet, humid conditions that are present for several days. Hot spots can be areas around feeders and water fonts, especially if these areas are not cleaned and maintained properly.

After sporulation, the oocyte hatches and invades the cell lining of the bird’s small intestine. It goes through several life stages and multiplies rapidly, destroying the cells as it continues to proliferate.

Chickens carry various strains of the coccidiosis organism, but not all birds may become infected with the disease. It is important to note that the different strains of Eimeria manifest in different areas of the intestinal tract, as well as different ages of the bird. Chicks are the most susceptible to the disease since they have not had exposure and time to develop a natural immunity. However, the adult bird can be infected and pass it on to other members of the flock through their droppings.

Coccidiosis can be spread by carrying the oocytes on clothing or equipment, such as shovels or boots, into the flock environment. Paying attention to biosecurity will limit the spread of the disease on farms.

Eimeria tenella, prevalent in the caeca and E. necatrix in the mid-section of the small intestine, is the most pathogenic and responsible for most mortalities due to coccidiosis. E. acervulina in the upper small intestine and E. maxima in the mid-small intestine can result in production losses.

What to look out for

Coccidiosis develops relatively quickly and has an incubation period of 4 to 8 days. Symptoms may develop gradually or appear suddenly, and it is not uncommon for the bird to seem fine one day and become very sick or even die the next. Signs of coccidiosis may vary from a decrease in growth rate to a high percentage of visibly sick birds depending on the severity with symptoms that may include:

- Severe Diarrhoea

- High mortality

- Depressed feed and water consumption

- Weakness and lethargic birds

- Pale comb or skin

- Blood located at the vent site of the bird

- Ruffled feathers

- Weight loss (in older chickens)

- Retarded growth rate (in young chickens)

- Failing to lay or laying eggs inconsistently

In some cases, subclinical infections may lead to a secondary infection by Clostridium spp. Resulting in necrotic enteritis. Birds surviving severe infection may recover in 10–14 days but may never recover the loss in performance. Lesions are almost entirely in the intestinal tract and often have a distinctive location and appearance that is useful in diagnosis. The most common symptom of the disease is blood or mucus in the droppings. Droppings may also appear brownish red due to the normal shedding of caecal cells, making it very difficult to make a diagnosis. To be sure, if the droppings indicate infected birds, they should be sampled and analysed, and a veterinarian should do a lesion score and/or histopathology.

Treatment options

Fortunately, coccidiosis can be treated. It is important to treat every bird in the flock to contain the outbreak and follow the recommendation of your consulting veterinarian. There are several options available to treat coccidiosis, which range from thorough cleaning and disinfecting of the house to control or prevent infection through to vaccination. Vaccination is more popular with broiler breeders, and a suitable programme can be set up by your veterinarian. The most popular treatment for broilers and pullets is to use coccidiostats, which are applied through the feed. Coccidiostats are antiprotozoal agents that act against the coccidia parasites by inhibiting reproduction and retarding the development of the parasite in a host cell.

Two categories of drugs are used to control coccidiosis in poultry: ionophorous compounds or molecules (ionophores) and synthetic agents (also known as chemicals).

Ionophores are divided into three classes:

- Monovalent ionophores, which include salinomycin, monensin and narasin.

- Monovalent glycoside ionophores, including maduramycin and semduramycin.

- Divalent ionophores such as lasalocid.

These compounds have a common mode of action, and if resistance develops to one ionophore, then this can also be the case for the others. This is known as cross-resistance. They work against sporozoites, the stage of the life cycle present in the gut lumen before they penetrate a host cell.

Chemicals, or synthetic drugs, have a very different mode of action. Resistance developed to these compounds is not shared with an ionophore or a synthetic drug of a different type. They destroy intracellular stages once they have invaded host cells and are undergoing development in the intestine.

Prevention programmes

When designing an effective anticoccidial programme, it is important not to use any one product for an extended period to reduce the possibility of resistance developing.

Three different programmes are used by the broiler industry:

- Single programme: One product is used for the whole cycle. On these programmes, ionophores can be used for two to three cycles.

- Shuttle programme: Two or more products are used in different feeds in the same flock. Often, these programmes involve using a chemical in the Starter feed followed by an ionophore in the Grower & Finisher feed. The advantage of this programme is that the risk of developing resistance can be reduced, especially if the two products have different modes of action.

- Rotation programme: This involves using different products in different cycles. For example, a single programme with drug ‘A’ may be used for one cycle, followed by a shuttle programme using drug ‘B’ in the Starter and drug ‘C’ in the Grower & Finisher for the next two cycles.

The most appropriate drugs to use

Unfortunately, there is no easy way to determine which drugs are the most appropriate. When designing the programme, it is important to consider the following points:

- Involve your veterinarian.

- Keep the programme simple.

- Monitoring the birds regularly to determine which Eimeria species are present and causing lesions in the gut will help in deciding which drugs or programme to follow.

- Avoid using chemical coccidiostats for long periods.

- Try not to use a chemical coccidiostat in the next cycle if one has just been used.

- Make optimal use of ionophores in the programme.

- Consider including vaccination for one cycle as part of the programme.

- Environmental conditions and husbandry practices will influence which programme to use at different times.

Prevention is better than cure.

Attention to detail in managing the birds and high levels of hygiene are also necessary to control coccidiosis. Close attention to the following points will help in reducing the risk of the birds’ experiencing problems from coccidiosis:

- Good biosecurity procedures should be in place outside and inside the poultry house.

- The house must be cleaned and disinfected and prepared for the next flock correctly.

- Longer periods between flocks are recommended rather than shorter periods.

- Good brooding practices will reduce the risk of infection.

- Clean, fresh water should always be available.

- Litter and feeders must be kept clean and dry.

- Birds reared under ideal environmental conditions will experience less stress and will have a better immune status.

Conclusion

Coccidiosis is a parasitic infection that can cause significant losses in poultry operations. The problem can be controlled by a combination of good management plus the use of carefully designed anticoccidial programmes.

Get in touch with your local De Heus Specialist to learn more about unlocking your farm’s potential - https://www.deheus.co.za/meet-our-team