A critical period for sows - Transition to lactation

The transition from gestation to lactation is marked by rapid and substantial physiological, hormonal, and metabolic changes in the sow. This transition period, defined as the last week of gestation and the first week of lactation, is especially challenging for hyperprolific sows. A farrowing duration of 10 to 20-minute intervals between piglets is physiologically normal and is crucial to ensure that piglets are born alive and are vital at birth. A smooth transition is also required for an optimal start of milk production. Nutrition and management of sows, both play an important role during this critical period and are crucial for a successful transition. This article gives more insight into the physiology of the sow during the transition period and how we can affect it.

The changes in the body during the transition - what is happening with the sows?

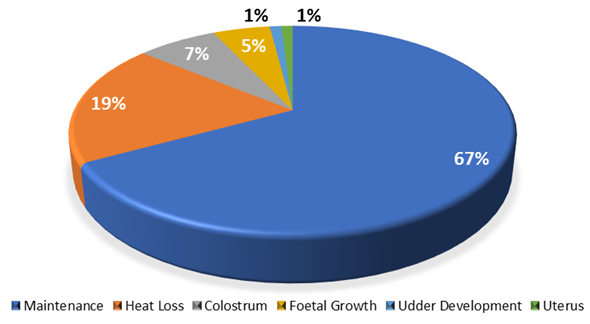

Foetal growth, mammary gland development, nest-building behaviour, colostrum production and uterine contractions are physiological processes that are prioritised by the sow during the transition period. These processes are controlled by hormones and demand high amounts of energy and nutrients. Energy and nutrients are provided by feed but, when nutrient intake is lower than nutrient requirements, they are drawn from body reserves. Energy and nutrients are allocated to the different tissues and processes in the body of the sow to support their physiological requirements (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of requirements of sows during the transition period.

Hormonal changes

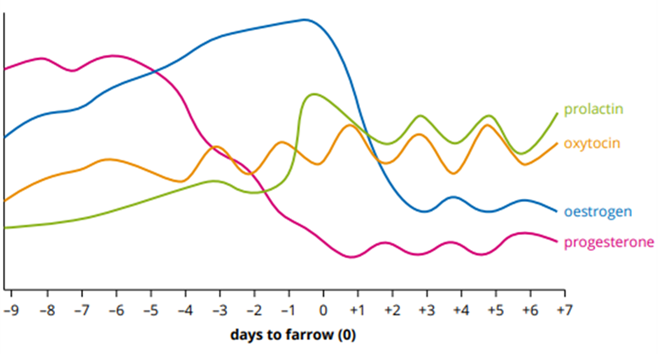

Oestrogens, oxytocin, and prolactin are key hormones that work together during this period to prepare the sow’s body to express nesting and maternal behaviour, give birth and produce colostrum and milk. When the levels of the hormone that maintains pregnancy, progesterone, begins to decline, this stimulates the hormones to increase (Figure 2).

The hormonal balance can be disturbed if sows experience stress, constipation, or when the body condition at farrowing is not optimal. Human interventions can also disturb the hormonal balance.

Stress is the most important trigger of hormonal imbalance, and sows are very sensitive to it.

Constipation increases intestinal bacterial overgrowth and endotoxin absorption from the intestine. This can lead to unwanted inflammation within the body, which can then cause a hormonal imbalance.

Sows that are too fat have higher progesterone and leptin hormone levels circulating in the blood. High circulating progesterone levels in the blood will inhibit the increase in oestrogens, oxytocin, and prolactin and thereby interfere with uterine activity and colostrum production. Leptin is a hormone that suppresses appetite, resulting in low feed and insufficient nutrient intake. Injecting oxytocin to initiate farrowing can also disturb the normal functioning of hormones. So be careful when using it!

Figure 2. Changes in reproductive hormone levels during the transition period

(Adapted from Peltoniemi and Oliviero, 2014)

Energy and nutrient utilization during the transition

The energy requirement is, perhaps, the most important aspect to consider for sows in transition as it is the basis for all the physiological processes involved and Figure 3 shows the estimated, relative energy requirement for each of them. Due to physiological processes within the body and physical, pre-farrowing activity, two-thirds of the energy is used for maintenance and 19% is lost as heat. The piglets are almost fully developed so only 5% will be going to fetal growth. The udder is almost fully developed just before farrowing, as is the uterus, and both organs have a very small energy requirement. Colostrum production will start taking place and this will require about 7% of the energy intake.

Figure 3. Partitioning of energy to maintain proper body physiological functions during the transition period.

During farrowing, the sow requires large amounts of energy and calcium to support effective uterine contractions to reduce the duration of the farrowing process and, consequently, increase piglet vitality and survival. On the day of farrowing, the energy demand required to support the farrowing process requires about 30% of the total energy requirements. The primary source of this energy comes from glucose (80%) from the diet and glycogen reserves from the body. If the available glucose and/or calcium is depleted during the farrowing process, the contractions will be slower and weaker prolonging the farrowing duration which, in turn, can lead to a higher piglet mortality (stillborn). Thus, it is important that the sow has sufficient reserves of these nutrients.

Low (insufficient) trace mineral and vitamin intake may affect hormonal functions, enzyme activity, and the antioxidant status of the sow. The requirements for these body functions are difficult to estimate, but research has shown that the needs of hyperprolific sows for several vitamins and trace elements are possibly higher than we expect.

Feeding sows during the transition

Feeding sows through the transition to lactation is a complex task. Hyperprolific sows have high requirements for energy, calcium, vitamins, and trace minerals during this period. Feeding hyperprolific sows less than three kilogrammes per day might not be sufficient to satisfy their nutrient requirements. When designing feeding programs to meet these nutrient requirements, we must focus on the nutrient intake per day rather than the kilogrammes of feed per day.

The week before farrowing, sows require at least 7,250 kcal NE per day. On the day of farrowing, the energy level should be lowered by 1,000 kcal NE/day to 6,250 kcal NE to reduce the risk of udder tension. After farrowing, the energy level should be increased by 1,000 kcal NE/day until sows reach their maximum feed intake. The maximum feed intake should determine the energy level of the feed to be fed, as we want to provide the sow with a diet that allows her to consume enough nutrients to meet her requirements during peak lactation. Once we know the energy content of the feed, we can calculate the feeding level required during the transition period. For example, 7,250 kcal NE is required per day and if the feed contains 2,200 kcal NE, then 7,250/2,200 = 3.3 kg of feed should be provided per day to sows during the transition.

The nutrient intake of the sow can be affected by feeding frequency. Increasing the frequency of feeding can not only increase the nutrient intake per day but also ensure more constant nutrient levels in the blood which can be used for uterine contractions. Trials have shown that feeding sows 4x a day, at 6-hour intervals, smooths the transition period.

Water must also not be forgotten! Sows in transition should be provided with at least 15 litres of water/ day to avoid constipation and ensure sufficient colostrum production. Under hot conditions, the amount of water provided should be even higher.

Tips and tricks to optimize the transition to lactation.

Every farm situation is different, and a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution is not possible. Each farm must be carefully evaluated to fulfill the nutritional requirements of sows and any kind of stress during the transition and lactation should be avoided. This will ensure a smooth transition from gestation into lactation with the following benefits:

- A shorter farrowing duration with less variation between sows.

- Less need for assistance during farrowing.

- Sows are less likely to experience constipation.

- Colostrum production will be higher, and litter growth and weaning weight will also be higher.

- Lower body weight and backfat losses during lactation.

Should you require more information relating to the critical period for sows the transition to lactation please contact your De Heus Technical Specialist - https://www.deheus.co.za/meet-our-team/.